What is the debt ceiling?

The federal debt limit (ceiling) restricts the total amount of money that the Treasury Department can legally borrow at any point in time.

Since the initial debt limit was set in 1939, it has been increased 104 times under presidents and Congresses controlled by both parties. In December of 2021, the debt limit was increased to $31.4 trillion, and we reached that limit on January 19, 2023.

Since then, the Treasury Department has been using emergency tools (extraordinary measures) to meet their obligations. However, these measures are temporary and are expected to run out in early June.

Has the debt ceiling been breached before?

The US has approached and averted potential debt crises before. In fact, looking back at recent history, we’ve been at this juncture many times since the year 2000. Perhaps the most similar to our current situation was 2011 when a divided Congress came within hours of default—but they did reach a deal.

Only once has the US defaulted on debt. This happened following the War of 1812, partly due to inconsistent federal revenues and a fragmented federal financial system.

Why does the debt ceiling matter, and what happens if it is not increased?

Democrats and Republicans have been in a standoff over what to do since the limit was reached in January.

If an agreement is not reached in time, the Treasury Department would be forced to limit outgoing payments to the amount they receive in revenues. The US might not be able to meet its obligations on time and in full. Treasury debt interest and principal payments could be temporarily suspended, and the full faith and credit of the United States would be called into question. Rating agencies may downgrade US government debt (as we saw in 2011), and the government’s cost of borrowing (i.e., interest rates) will increase. In the worst-case scenario, government benefits such as social security and Medicare could also be temporarily interrupted.

The Treasury Department might have to explore new measures, such as:

- Prioritizing debt repayment over other government obligations (so technically the US does not default).

- The President using the 14th amendment to ignore the debt ceiling, which would allow the US to meet its obligations and would surely end in a legal battle.

- The Treasury minting a $1 trillion coin to deposit with the Federal Reserve so the US could meet its obligations (also likely to end in a legal battle).

To read more on possible measures, visit the Bipartisan Policy Center page.

How do markets react when the debt ceiling looms?

There are no tools to accurately anticipate how markets will react to a US default on obligations, but we can look to recent history when the debt limit has also loomed for some clues.

In the period leading up to the 2011 debt ceiling crisis, the stock market downturn started about a month before the “X-date.” Market volatility increased as the deadline drew closer. When all was said and done, the S&P 500 declined over 16% through the crisis. With a resolution finally reached in early August, the stock market rebounded, and 2011 ended flat.

At the same time, in the bond market, yields increased (and prices decreased) on short-term Treasury bills with maturities around the X-date, as investors required more return for the risk taken on. The increase in yields had a cascading effect on other debt issuances and consumer loans.

Current markets are sending signals of investor concern. Treasury bills maturing in mid to late summer are already starting to see a premium in their yields that may reflect increased anxiety surrounding a resolution.

What are an investor’s best defenses against a debt ceiling impasse?

The world has given us no shortage of worries in the last several years, and the debt ceiling is the most recent crisis. It’s very tempting to negotiate our investment holdings around the latest crisis. However, experience has taught us that this is not prudent because 1) markets incorporate news quickly and usually before we can make a change and 2) getting out of the market means we have to also time getting back in. It is very hard to get either, let alone both, of these decisions correct.

What can an investor do in the face of this risk?

- Review your goals and circumstances. If they are largely the same as last year, last month, or last week, resist making investment decisions based on emotion.

- Make sure your asset allocation is appropriate for your time horizon and goals.

- Remember that markets are forward-looking and price new information into the market quickly.

- Diversification is your best defense against unknown or new risks. A globally diversified portfolio will aid in mitigating the risk stemming from a US default.

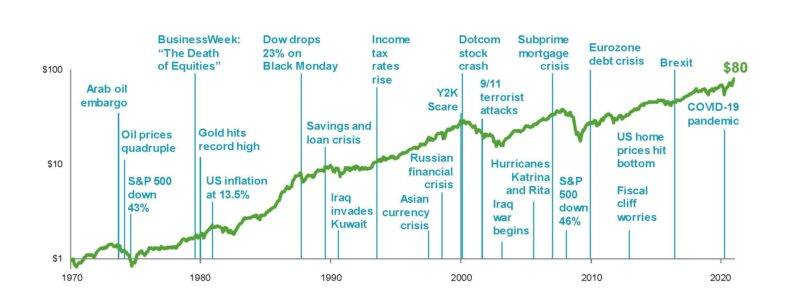

- Remember that the world has experienced a myriad of crises in the last half century. Despite this, capital markets have rewarded the disciplined investor over the long term.

Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors. In US dollars. MSCI data © MSCI 2020, all rights reserved. Indices are not available for direct investment. Their performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management of an actual portfolio.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

A key part of a good long-term investment experience is being able to stay with your investment strategy, even during tough times. A well‑thought‑out investment approach can help people be better prepared to face uncertainty and may improve their ability to stick with their plan and ultimately capture the long-term returns of capital markets.